In my research, I discovered two very interesting trends regarding how the Kokopelli is used by certain “Native institutions.” For the sake of clarity, “Native institutions” within the framework of this thesis refers to entities relating to various Native experiences, such as museums, preserved artifacts, national monuments, etc.

NOTE(S): The institutions referenced on this page are largely not Native-owned or operated. Native people have been involved in the construction of many of the following spaces (such as the National Museum of the American Indian), but these institutions are, for the most part, run by local or federal government entities. The level of consultation with Native people varies from institution to institution, but the day to day operations of these sites are controlled by the public.

The first thing I discovered is that these institutions seem to have capitalized on the cultural hype surrounding the Kokopelli, using the image as a luring mechanism to bring to light other aspects of Native experiences.

Capitalizing on the Hype

As mentioned on a previous page, Walnut Canyon National Monument in Flagstaff has two Kokopellis painted on its entrance sign, accompanied by the operating hours and the phrase “Cliff Dwellings.”1 The national monument, which preserves the cave dwellings of the pre-Columbian, Ancestral Puebloan Sinagua people, has safeguarded petroglyph sites for visitors to see the surviving rock art. As the flute player symbol on the sign is purportedly replicated from a petroglyph in the canyon, it is, of course, understandable why those in charge of Walnut Canyon painted Kokopellis onto the entrance sign.

Source: Google Images

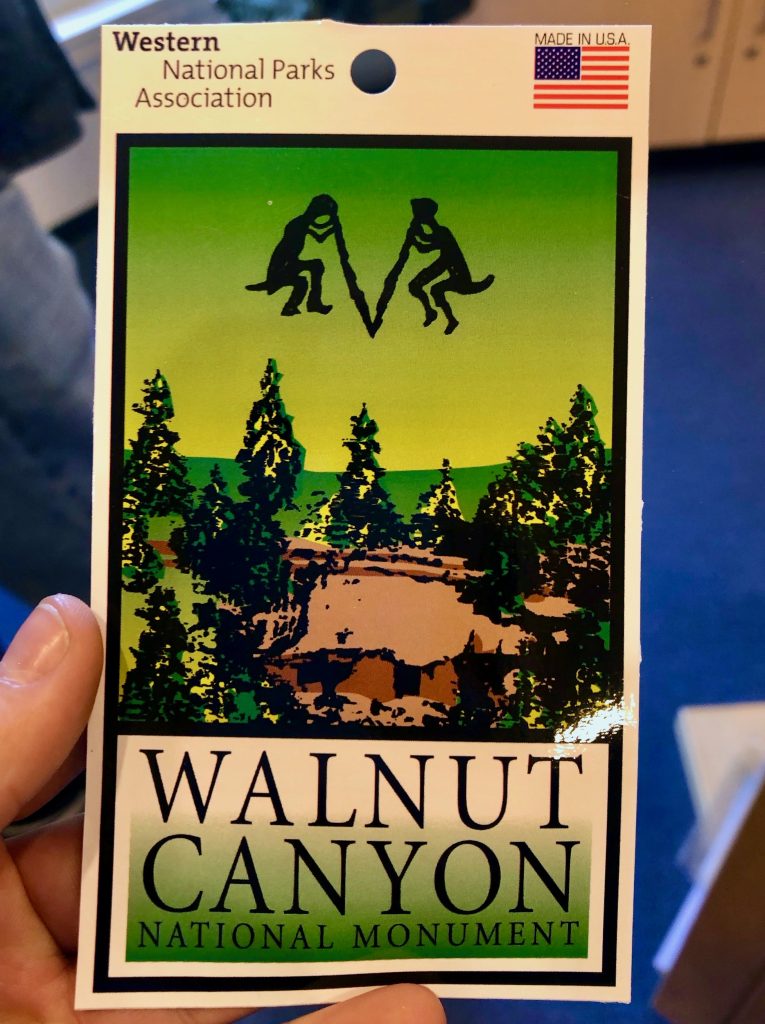

Walnut Canyon doesn’t only use the symbol for the entrance sign, however. It is also featured heavily in gift shop souvenirs, so much so that one may get the impression that it is the monument’s logo.

It is important to note that despite its petroglyphic presence in the canyon, the flute player symbol is not at all the “main event” of the experience at the monument. I visited Walnut Canyon in March of 2019 and did not find any mention of the symbol or its significance in the museum exhibit. I asked a staff member about the usage of the symbol, to which she mumbled something about it being “cool.” This is, of course, not the official viewpoint of Walnut Canyon, but I found it telling that the site itself can’t seem to reason as to their extensive usage of the image.

One can thus infer that the decision to use the Kokopelli on the entrance sign and in the gift shop trinkets was a calculated one. Beyond the somewhat loose connection to the canyon image, it seems as though the cultural fascination with the symbol and its popularity may have played a role in these decisions. The usage of the Kokopelli may mean that visitors are more likely to recognize the image on the sign and want to venture in to learn more about the site. Or perhaps, they’re more likely to buy a Kokopelli trinket, whose funds can be used to preserve or enhance some aspect of the experience. Regardless, there is a reason why the flute player image was chosen out of all of the canyon images to be represented so greatly. And we can only assume that this decision was intended to benefit Walnut Canyon in some way, by using the fascination with the symbol to draw attention to the site.

Similar to Walnut Canyon, the entrance to the Pueblo Grande Museum in Phoenix has Kokopellis painted above the doors. The museum has been in continuous operation for over 80 years, preserving pre-Columbian archeological ruins constructed by the Hohokam people and educating visitors about their practices and culture in the accompanying museum.2

Source: Richard A. Rogers

While the Kokopelli is not at all a central focus of the museum or artifacts, the museum nonetheless uses the symbol as a ‘greeter’ of sorts to both lure and welcome visitors into the museum. The Pueblo Grande Museum thus uses the cultural enchantment with the Kokopelli to their own advantage, in order to draw people to their establishment and encourage interest in learning more about Indigenous cultures.

According to expert Richard Rogers, Kokopelli Statue in Price, Utah serves as another example of this. The statue serves as a “gateway” to Nine Mile Canyon, the “world’s largest art gallery,” known for its extensive rock art created by the Fremont Culture and the Ute People.3 This statue ultimately has a complex dynamic, as it is both private art birthed in the mind of a seemingly white artist, as well as a public monument of sorts, paying tribute to Native cultures and urging visitors onward to Nine Mile Canyon.

Artist: Gary Prazen

Artist: Gary Prazen

In a sense, this statue serves a similar purpose of the artwork outside of Walnut Canyon and Pueblo Grande Museum, as it uses the hype of the Kokopelli—only a small part (if any at all) of the nearby tourist destination—in order to draw people in toward the whole experience.

Perpetuating the Commodity

The second interesting thing I discovered regarding how various Native institutions use the Kokopelli is that even institutions and informative sites devoted to supporting Indigenous experiences can be seen perpetuating the typical commodified misrepresentation of the Kokopelli as the hunchback flute player.

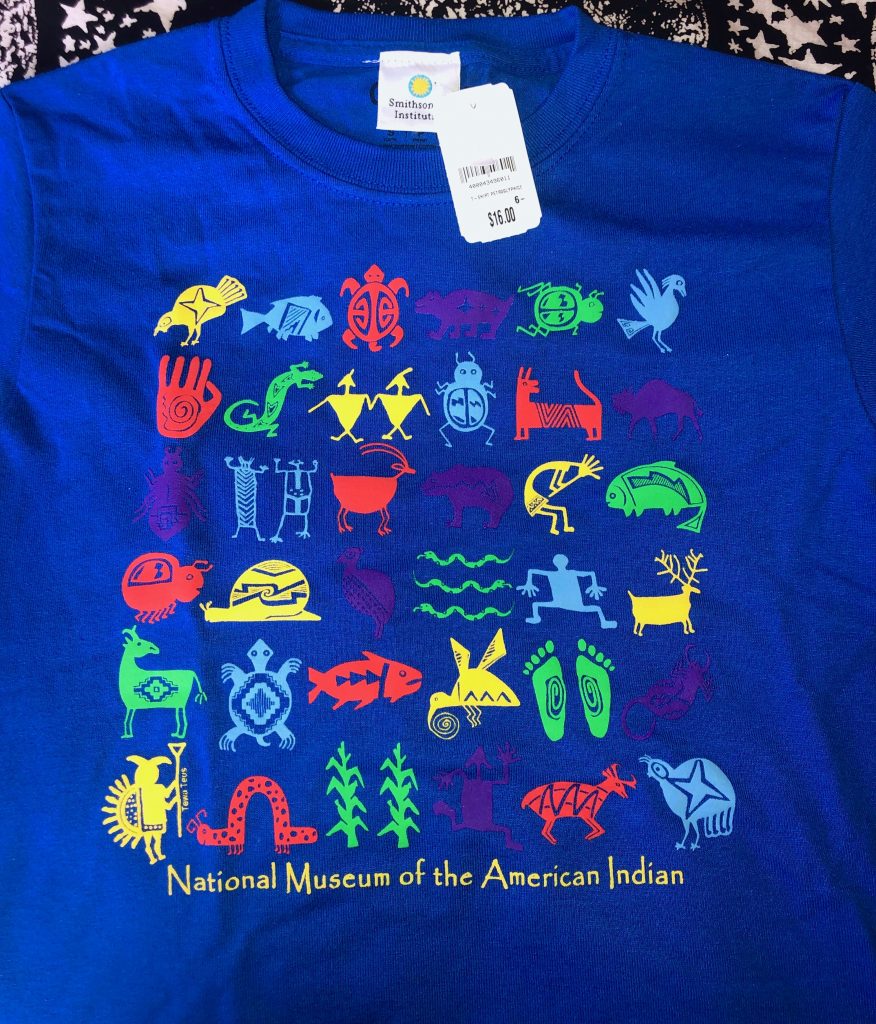

The first example of this can be found at the National Museum of the American Indian located in Washington, D.C., a Smithsonian Institution devoted to “[giving visitors from around the world the sense and spirit of Native America”].4 While the museum does a great job at shedding light on various Native cultures and experiences, it nonetheless perpetuates the commodification and conflation of Native cultures in the form of non-sacred items like car decals, children’s t-shirts, and stuffed toys.

One of such items can be found in the Roanoke Museum Store on the second floor—a bright blue kids’ t-shirt decorated with different “rock art” images, the Kokopelli being one of the only identifiable ones. Evidently intended for children, the design is over-simplified and thus fails to distinguish between the multiplicity of cultures and symbols that are referenced in this one shirt. One would think that such a reputable museum would be concerned about potentially undermining their mission of educating the public on the particularities of various Native cultures in a trivial place like a gift shop, but it appears as though the commodification and conflation of Native cultures permeate even the best intentioned.

This trend can also be seen in how seemingly ‘reliable’ websites and institutions offering information about the Kokopelli continue to perpetuate misinformation about the flute player image, such as Wikipedia’s “Kokopelli” entry, many sites about Hopi kachina dolls (kachina.us and kachina-dolls.com), as well as ones providing information about rock art for tourists and tour guides (zionnational-park.com, desert.usa.com, riverguides.org). These websites misidentify the Kokopelli as a flute player, as well as labeling flute players as the Kokopelli5, rendering it challenging for interested individuals to find accurate information.

| 1 | National Park Service. Walnut Canyon National Monument: Entrance Sign. Flagstaff, AZ. |

| 2 | "Pueblo Grande Museum.” City of Phoenix. Accessed November 09, 2018. https://www.phoenix.gov/parks/arts-culture-history/pueblo-grande/about-the-museum. |

| 3 | Richard A. Rogers, “Kokopelli—Senior Thesis Project,” e-mail interview by author, October 15, 2018. |

| 4 | Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, Brochure: Exhibitions, Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 2018. |

| 5 | Richard A Rogers, Petroglyphs, Pictographs, and Projections: Native American Rock Art in the Contemporary Cultural Landscape, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2018, 180. |